Chapter Twenty-Three

May, 2000

We got an early train from Vernazza to Monterosso, then transferred to another train bound for Genoa. The train was over-full, and we rode in the snack-bar car (too much prepackaged food to call it a dining car), buying just enough junk food to keep us from being kicked out.

The plan was to continue on to Nice from Genoa, visiting the southern coast of France as we moved westerly along the Mediterranean coast.

Funny how plans change. We arrived in Genoa before lunch and discovered a four-hour wait for a train to Nice. Because our guidebooks had so little to say about Genoa, we bought tickets for a cruise ship to Barcelona departing at 10:00 p.m. (At the time, this made perfect sense.) We left the train station to hunt for lunch and something to amuse us for the next eight or nine hours.

After the peace and beauty of the Cinque Terre, Genoa is a shock. It's loud and crowded, dark and dirty. Once a

merchant capital, it's been in decline for centuries. Not to say it isn't a thriving, bustling city. It's just

lacking in grand monuments and exciting history. Genoa tries to make up for it by celebrating their local boy

made good, but even if Christopher Columbus did discover the New World, it wasn't the Italians who got the

credit.

After the peace and beauty of the Cinque Terre, Genoa is a shock. It's loud and crowded, dark and dirty. Once a

merchant capital, it's been in decline for centuries. Not to say it isn't a thriving, bustling city. It's just

lacking in grand monuments and exciting history. Genoa tries to make up for it by celebrating their local boy

made good, but even if Christopher Columbus did discover the New World, it wasn't the Italians who got the

credit.

Genoa does have, however, an extremely fantastic aquarium. With features focusing on habitat instead of flashy creatures, an afternoon at the aquarium is like a tour of Earth's more liquid parts. There were the usual highlights: sharks, turtles, eels, dolphins, jellyfish, seals, and rays. But we also explored aquatic lifestyles from the Amazon Basin to the Pacific Abyss, from Madagascar to the Mediterranean. We were observing the displays on the technological similarities between exploring space and exploring the deep when a security guard escorted us to the door he wanted to lock for the night.

The cruise ship Fantastic was impressive. The largest ship I've ever been aboard, she had a casino, two

bars, two restaurants, a shopping arcade, a beauty salon and fitness center: everything you need to "see the

world" without leaving upper-middle class comfort behind. On board, we were still tourists, investigating a

foreign way of seeing the world. Ian called it "ideological tourism". I simply got seasick.

The cruise ship Fantastic was impressive. The largest ship I've ever been aboard, she had a casino, two

bars, two restaurants, a shopping arcade, a beauty salon and fitness center: everything you need to "see the

world" without leaving upper-middle class comfort behind. On board, we were still tourists, investigating a

foreign way of seeing the world. Ian called it "ideological tourism". I simply got seasick.

We arrived after 18 hours at sea, disembarking at the end of the Ramblas under the watchful gaze of the Columbus Memorial looking out over the Mediterranean. No one but me seemed to notice the ground rocking underfoot as we walked to the heart of Barcelona. As I was the one with four years of Spanish classes in high school, it was my job to translate signs and find us a place to sleep despite my rusty Spanish skills. I never achieved fluency while in school, and while I could remember words, grammar and conjugations were gone. I found us a hotel using keywords and infinitive verbs. And I remembered, again, that no matter the language, I will always understand what I read better than what I hear.

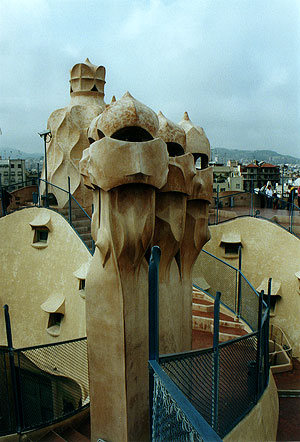

We spent the majority of our time in Barcelona exploring the work of

Antoni Gaudí, a modernist architect who left

quite the mark on the city. His buildings look more like something grown, not built. Angles are rare. Walls

curve, rooflines undulate. It's a startling combination, the organic-ness of the shapes and the colors he used

with the rigidity of concrete, almost like being able to simultaneously see both flesh and bones. Balconies leer

like skulls from the sides of buildings, chimneys twist like old grapevines then taper off like so much

soft-serve. I'm sure right angles are easier and faster than others, but it makes one wonder what our cities

might look like if curves weren't such a novelty.

We spent the majority of our time in Barcelona exploring the work of

Antoni Gaudí, a modernist architect who left

quite the mark on the city. His buildings look more like something grown, not built. Angles are rare. Walls

curve, rooflines undulate. It's a startling combination, the organic-ness of the shapes and the colors he used

with the rigidity of concrete, almost like being able to simultaneously see both flesh and bones. Balconies leer

like skulls from the sides of buildings, chimneys twist like old grapevines then taper off like so much

soft-serve. I'm sure right angles are easier and faster than others, but it makes one wonder what our cities

might look like if curves weren't such a novelty.

Perhaps Gaudí's most famous work, of course, is La Sagrada Familia, a cathedral designed and begun by Gaudí but still under construction. (Gaudí was killed by a streetcar in 1926.) After seeing so many completed cathedrals, it's especially striking to see one in progress. Sure, building Köln's Dom must have been a lot of work, but I didn't really think about the details until we saw the crane towering over where the high altar will one day be at Sagrada Familia and realized that they built the Dom without electricity or hydraulics.

We left a donation in the box; the continuing work on La Sagrada Familia is funded entirely by donation. It's comforting to think that the cathedral is a project of all the people who come to see it, not a project of Barcelona the city or Spain the state. It's impossible to know how many of the donations are given to honor God and how many are to honor Gaudí. I don't know which it was in our case, either. Perhaps the gifts are given out of curiosity to see what the cathedral will ultimately become. Perhaps it's a way of saying, "I had a hand in that."

Because, of course, the cathedral wasn't completely planned out when that streetcar hit Gaudí as he

crossed the street to the construction site one morning. The facade of the Nativity is definitely

Gaudí's, the characters of the Christmas Story nestled in a riot of organically curved stone that always

seems to leave me thinking, rather blasphemously, of an elaborate ice cream sundae left too long in the

Mediterranean sun. On the opposite side of the building is the facade of the Crucifixion, designed by

Josep María Subirachs. This side is less

voluptuous, rendering the Stations of the Cross in stark lines. Gaudí's influence is there, but it's as

if Subirachs stripped away the exuberance and abundance to reveal structure and substance underneath. The

flowers, fruits and birds of the Nativity side have disappeared, leaving smooth planes, sharp edges, empty

space.

Because, of course, the cathedral wasn't completely planned out when that streetcar hit Gaudí as he

crossed the street to the construction site one morning. The facade of the Nativity is definitely

Gaudí's, the characters of the Christmas Story nestled in a riot of organically curved stone that always

seems to leave me thinking, rather blasphemously, of an elaborate ice cream sundae left too long in the

Mediterranean sun. On the opposite side of the building is the facade of the Crucifixion, designed by

Josep María Subirachs. This side is less

voluptuous, rendering the Stations of the Cross in stark lines. Gaudí's influence is there, but it's as

if Subirachs stripped away the exuberance and abundance to reveal structure and substance underneath. The

flowers, fruits and birds of the Nativity side have disappeared, leaving smooth planes, sharp edges, empty

space.

And perhaps this is why there are enough donations to keep the construction going: if there is such a contrast

between two sides of the cathedral built less than 100 years apart, what will the completed Sagrada Familia look

like? A mélange of styles, out-Baroque-ing even the Baroque era? Will there be any cohesion? What do the

different phases say about the periods of their creation? What do they say about the changing role of the

Church? About people's perception of and interaction with it?

And perhaps this is why there are enough donations to keep the construction going: if there is such a contrast

between two sides of the cathedral built less than 100 years apart, what will the completed Sagrada Familia look

like? A mélange of styles, out-Baroque-ing even the Baroque era? Will there be any cohesion? What do the

different phases say about the periods of their creation? What do they say about the changing role of the

Church? About people's perception of and interaction with it?

We caught a night train to Madrid where we visited the Prado (Titian, Boticelli, Bosch, El Greco, Velasquez and Goya Light and Dark) twice and the Reina Sophia Modern Art Museum (Miró, Dalí, Picasso and a refrigerated ladder, leading Ian to muse aloud about modern art being the debris of the artist's journey taken out of context when placed in a museum and to wonder about museum bureaucrats) once. We ate museum food, tapas and ice cream (Ian found Roquefort gelato!); vegetarian dining is not a Spanish specialty.

The night train to Paris was the first night train that afforded me any sleep. The compartment came with little bags of toiletries, a sink, mirrors, spacious bunks and a chamber pot. We switched trains in Paris and arrived in Köln four hours later, where it was shockingly hot and swimming in tourists. We dropped off 23 rolls of film before catching the train to Bad Breisig and Rheineck and home. Three days later, after doing loads of laundry and nursing our Spanish colds back to something vaguely healthy, we were off again, catching the 4pm train to London.

Getting on the Chunnel train is a lot like getting on a plane, what with all the security and boarding passes and special doors. Easy train travel makes modern Europe feel accessible and low-impact. Getting to the United Kingdom is harder, reminding you that it's an island, that even now it's a part of Europe but still set apart somehow. The Chunnel train zooms through Belgium, spends 20 minutes in the actual Chunnel, then crawls its way to London. We found ourselves a bed and breakfast near Victoria Station; the Eastern European landlady fed us beans on toast for breakfast, completely flummoxed that we wouldn't eat meat.

Our first full day in London was "Art in Context Day", made up of visiting locations with art specifically

planned for its display location. The central gallery at the Tate Modern with a 350-foot tall spider designed

for that space. Westminster Abbey crowded with monuments all trying to out-ostentate each other, with

Poets' Corner wedged between the statesmen

and churchmen like a cosy stone review of my English degree. Trafalgar Square with its fountains and lions (and

active public fountain consumption and water fights dousing unsuspecting tourists - it was warm for London!).

Our first full day in London was "Art in Context Day", made up of visiting locations with art specifically

planned for its display location. The central gallery at the Tate Modern with a 350-foot tall spider designed

for that space. Westminster Abbey crowded with monuments all trying to out-ostentate each other, with

Poets' Corner wedged between the statesmen

and churchmen like a cosy stone review of my English degree. Trafalgar Square with its fountains and lions (and

active public fountain consumption and water fights dousing unsuspecting tourists - it was warm for London!).

The day finished with more "art in context" with a showing of The Tempest starring Vanessa Redgrave as Prospero at The Globe. I had seen The Two Gentlemen of Varona there with Westmont's England Semester in 1996. Shakespeare's Globe was then still under (re)construction, but now all the balcony rails had all their hand-finished banister supports in place. We were groundlings, standing through the entire play, enjoying a production not just using its theatre space but appearing in the space Shakespeare wrote it for. The actors engaged the audience in some unusual ways as well, at one point throwing dead fish at us.

The Tate Modern had recently opened, and we spent a day there. Mondrian, Dalí, uncredited Geiger, Rothko, Pollock, Picasso, Monet, Lichtenstein, Erust, and a whole host of installations, which Ian noted as "nice" and "ranging from silly to disturbing". There were some ruminating discussions about how Raphael and Michelangelo must have crossed paths while working on their various "installations" for the Vatican; which of the artists behind Tate Modern's installations crossed paths, had discussions, in the set up time before the museum opened? What will those discussions produce? In three hundred years, will anyone wonder the same thing about those artists?

Dinner was at Wagamama, a noodle bar with long, communal tables and wireless-enabled waitstaff. Then, from "Art!" to "Art?" with a viewing of Mission to Mars at the Leicester Square Odeon. The best part was probably all the goofy commercials before the movie. (I know everyone Stateside whines about commercials before the movie, but I find I kind of miss those little distillations of up-to-the-minute pop culture that preceded every movie we saw in Europe. But then, perhaps the commercials in Europe were wittier, funnier, edgier than what we Americans are regularly served, in theatres or on TV.)

Our train ride to Penrith gave me the opportunity to rediscover why I love the English countryside, all those

green hills speckled with sheep and sleepy farmhouses. Clearly, I read too much fantasy, because it's so easy to

watch the scenery go by and imagine the riotous back gardens behind those houses (all flowers and herbs and no

thorns or stinging insects, in bloom all the time) and the fresh bread in the kitchens. I love the countryside

for what it makes me think, the comfort of cocoa and a good book and a warm blanket. I know it's not

real, but please don't tell me about it.

Our train ride to Penrith gave me the opportunity to rediscover why I love the English countryside, all those

green hills speckled with sheep and sleepy farmhouses. Clearly, I read too much fantasy, because it's so easy to

watch the scenery go by and imagine the riotous back gardens behind those houses (all flowers and herbs and no

thorns or stinging insects, in bloom all the time) and the fresh bread in the kitchens. I love the countryside

for what it makes me think, the comfort of cocoa and a good book and a warm blanket. I know it's not

real, but please don't tell me about it.

At Penrith, we caught a coach to Keswick in the Lake District for our holiday-within-a-holiday. We had lazy mornings, pub meals, and lots of walking. We walked along some roads, through some woods, along the edge of pastures populated by sheep and the occasional cow, over creeks and creeklets, and through a couple of rainstorms. It would be interesting to know more about private versus public land in Lake District. Is it that owners of livestock are permitted to graze their animals on public land (organic lawn mowing?)? Or are most of those lands privately held with permission given for more or less maintained paths and regular foot traffic? Does someone from the park service come through to collect litter? Or do visitors live up to expectation and behave respectfully?

(I sometimes wonder these days if the implied expectation that people can't or won't behave themselves causes the creation of rules and the employment of people to enforce those rules. If there were fewer rules and more societal expectations that people would just Do The Right Thing, would that be sufficient? There have been some experiments with this sort of thing for traffic. If you take away the signs and the lights and the lines on the road, traffic magically slows down and there are fewer accidents because people can't rely on the external guides to make others behave.)

Our walking took us to Castlerigg, an authentic stone

circle probably built sometime around 3000 BCE for a now-unknown purpose. Trade? Astrological observations?

Religious ceremony? All of the above? Now it's a walker's destination and a grazing ground for sheep. We paused

to read the 50p brochure and locate the "entrance stones" and "the outlier", none of which appear to have made

it into this picture. Then, off again, for more hills, more sheep, more rain, to Walla Crag and Falcon Crag,

where we enjoyed literally breathtaking views of Derwentwater (it was all uphill to get to said views!). Our

return path took us down to the water's edge and past more sheep. The

spring lambs had recently arrived, and I think I used almost a entire roll of

film taking pictures of bright white lambs who couldn't decide if they should mug for the camera or run to hide

behind Mama.

Our walking took us to Castlerigg, an authentic stone

circle probably built sometime around 3000 BCE for a now-unknown purpose. Trade? Astrological observations?

Religious ceremony? All of the above? Now it's a walker's destination and a grazing ground for sheep. We paused

to read the 50p brochure and locate the "entrance stones" and "the outlier", none of which appear to have made

it into this picture. Then, off again, for more hills, more sheep, more rain, to Walla Crag and Falcon Crag,

where we enjoyed literally breathtaking views of Derwentwater (it was all uphill to get to said views!). Our

return path took us down to the water's edge and past more sheep. The

spring lambs had recently arrived, and I think I used almost a entire roll of

film taking pictures of bright white lambs who couldn't decide if they should mug for the camera or run to hide

behind Mama.

After a day of idly wandering around Keswick, we caught our coach back to Penrith, arriving three hours before

our train was to depart for London. Fortunately,

Penrith Castle is right across the street from the

train station and happy to have visitors. Last occupied by Richard III (before he was king) in the mid 1400s,

it's a storybook ruin, all crumbling walls and visible foundation stones. It even has a moat, perfectly mown.

After a day of idly wandering around Keswick, we caught our coach back to Penrith, arriving three hours before

our train was to depart for London. Fortunately,

Penrith Castle is right across the street from the

train station and happy to have visitors. Last occupied by Richard III (before he was king) in the mid 1400s,

it's a storybook ruin, all crumbling walls and visible foundation stones. It even has a moat, perfectly mown.

Back in London, we caught an evening showing of Gladiator at Leicester Square. The next morning, we met an old friend of Ian's at Gatwick. Steve was arriving in Europe for the first time, and we gave him a 15 minute tour of London (get off the Tube at Westminster, wave at Big Ben, the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey, then get back on the Tube) before heading off to find train tickets back to the Continent (getting one-way tickets required going to the French train office, since apparently the British train office assumes you must want to come back to Britain). We probably talked Steve's ear off for the entire trip to Köln, passing on all the useful (and probably some not-so-useful) things we could think of. I guess we'd been in Europe a while if we had enough "wisdom" to fill the entire train ride.

Steve came all the way to Bad Breisig and Rheineck with us. We finally arrived at the bahnhof in Bad Breisig well after midnight to find that the phone for calling a taxi didn't work. We walked to the castle where we were greeted with an impromptu organ concert; there could have been no better way to show off our home of the last several months than that.

After launching Steve toward Amsterdam, we headed off to Paris for three days of highlights. The Bastille (or,

more accurately, the outline of the Bastille's foundation under a lot of cars in a very busy traffic circle).

Notre Dame and all its glorious stained glass. The Left

Bank and Shakespeare & Co (a writer's haven for ex-pat American authors like E. Hemingway). The Latin Quarter.

Place St. Michel, home to centuries of demonstrations.

Sainte-Chapelle, a

church built for Louis IX after he purchased the Crown of Thorns. (It's apparently constructed out of nothing

but air and light, with 1100 stained glass scenes covering the entire Bible.) The art nouveau subway entrance at

the Cité Metro stop. The Conciergerie where Marie-Antoinette and several other people were imprisoned

before marching off to the guillotine at Place de la Concorde (formerly Place de la Revolution).

The Virgin MegaStore. Tuileries Gardens, where an armada of

small sailboats waited by a fountain for someone to come sail them. The Champs-Élysées after

sunset. The Arc de Triomphe.

After launching Steve toward Amsterdam, we headed off to Paris for three days of highlights. The Bastille (or,

more accurately, the outline of the Bastille's foundation under a lot of cars in a very busy traffic circle).

Notre Dame and all its glorious stained glass. The Left

Bank and Shakespeare & Co (a writer's haven for ex-pat American authors like E. Hemingway). The Latin Quarter.

Place St. Michel, home to centuries of demonstrations.

Sainte-Chapelle, a

church built for Louis IX after he purchased the Crown of Thorns. (It's apparently constructed out of nothing

but air and light, with 1100 stained glass scenes covering the entire Bible.) The art nouveau subway entrance at

the Cité Metro stop. The Conciergerie where Marie-Antoinette and several other people were imprisoned

before marching off to the guillotine at Place de la Concorde (formerly Place de la Revolution).

The Virgin MegaStore. Tuileries Gardens, where an armada of

small sailboats waited by a fountain for someone to come sail them. The Champs-Élysées after

sunset. The Arc de Triomphe.

Ian met up with some folks with connections to Meta, Bryce and KPT. I went for an afternoon at the

Musée d' Orsay

with the Impressionists. We visited the Eiffel Tower at night, still all over-illuminated from the Millennium

celebrations, a destination somehow appropriate after seeing Van Gogh's

Starry Night, even if they really have nothing in common. And, of

course, the Louvre. We spent 6 hours

there (which my notes seems to indicate was a lot and rather surprising): Greek statues (including

Venus de Milo and

Winged Victory), Roman emperors, the Renaissance (including

Michelangelo's Slaves), Italian painting, French history, the Louvre's

medieval castle foundations, ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and Babylon.

Ian met up with some folks with connections to Meta, Bryce and KPT. I went for an afternoon at the

Musée d' Orsay

with the Impressionists. We visited the Eiffel Tower at night, still all over-illuminated from the Millennium

celebrations, a destination somehow appropriate after seeing Van Gogh's

Starry Night, even if they really have nothing in common. And, of

course, the Louvre. We spent 6 hours

there (which my notes seems to indicate was a lot and rather surprising): Greek statues (including

Venus de Milo and

Winged Victory), Roman emperors, the Renaissance (including

Michelangelo's Slaves), Italian painting, French history, the Louvre's

medieval castle foundations, ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and Babylon.

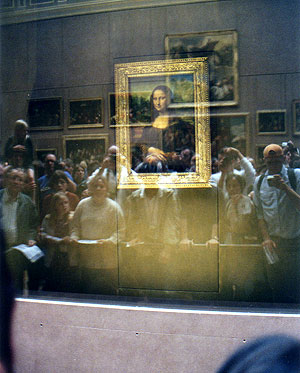

We stopped to greet Mona Lisa's adoring crowds; you can see Ian in the picture, just to the right of the gold frame. (There are postcards of Mona Lisa looking out over a sea of heads. Which does tell part of the story... there are lots of people there to see her. But she's also behind alarmed, shatterproof glass and a railing, so we're partial to this picture; it's so much more complete.)

And then it was over.

We found one last authentic French croissant and coffee breakfast and caught a train back to Germany and Köln, back to Bad Breisig and Rheineck.

We'd left Rheineck, excepting the occasional return to do laundry, six weeks before, just as Spring was really

getting going. Now it was starting to look as if all those winter months of the cold and the dark, the wet and

the grey, had never happened.

We'd left Rheineck, excepting the occasional return to do laundry, six weeks before, just as Spring was really

getting going. Now it was starting to look as if all those winter months of the cold and the dark, the wet and

the grey, had never happened.

So this is how we remember Rheineck, because this is what it looked like the morning we left, carrying way too many suitcases for two people, for the train station and the airport.

We flew to Seattle to visit with family there before heading down to the Bay Area. Some things were instantly familiar, old habits picked back up as if we never left. Other things took some adjusting to, like the width of American streets. Seven years later, I still sometimes try to bag my own groceries at the supermarket, much to the bewilderment of the store employees; every grocery store we shopped in while we were in Germany expected the customer to do the bagging. And I still sometimes forget that, in the US, I can make a right turn after stopping at a red light. We miss ciders black at Killybegs, the Mexican restaurant in Ramagen, and the Columbian restaurant in Bad Breisig.

Life goes on. Rheineck is where we left it, and the project we helped start is still ticking along, doing its thing and making its people happy. Ian and I married in 2002 after briefly participating in the Bay Area Dot Com Madness in San Francisco. We moved to Los Angeles to sample the film industry, then headed back into technology via a side trip to Kauai. Our daughter arrived in 2005.

Someday we'll take her to Europe; we'll take the train from Köln to Bad Breisig and walk up the hill to Rheineck. We'll go for a wander in the woods, out to the pastures and talk to the cows along the road to Waldorf. We'll stay for tea. And we'll tell her, sometimes life takes you to live in a castle on the Rhein River... and when the opportunity comes, you go for it.