We had been hearing about Karneval ever since we arrived in Germany, it seemed. The bar next to our hotel/apartment in Bad Neuenahr had a Karneval party at least one night a week, with special prices on the Brazilian drinks. One November night in Ramagen, we crossed paths with three locals, one of whom was dressed like a chicken, another in a pink tutu, and the third struggling to keep his companions upright as they crossed the square. And then there is the oft-repeated story about the predetermined time every year when all the women in Köln put down their tasks, pick up their scissors, and attack the nearest tie-wearing man. After the sacrifice of the ties, the drinking lasts for a week.

With advertising like this, how could we have allowed ourselves to miss out on these festivities? Besides, I'd missed my chance to wear my Renaissance costume for Halloween while we were in Mallorca.

|

Karneval has its roots in Church tradition. Lent is the forty day (plus Sundays) period preceding Easter, a period of fasting and purification, a time to remember the suffering of Christ and his crucifixion before celebrating the rebirth of the Resurrection. Once upon a time, the list of things forbidden by the Church for Lent was quite extensive: meat, fish, eggs, butter, alcohol, sometimes everything except one evening meal. The days just before Lent became days of excesses as people squeezed in all the fun they could before bowing to the requirements of solemnity and contemplation. And while some people still fast for Lent, giving up sugar, fast foods, or cigarettes, or adding extra prayer and devotional time to the daily routine, it's the party beforehand that everyone still celebrates, from Mardi Gras in New Orleans to Carnival in Rio de Janeiro to Karneval in Köln.

Karneval has its roots in Church tradition. Lent is the forty day (plus Sundays) period preceding Easter, a period of fasting and purification, a time to remember the suffering of Christ and his crucifixion before celebrating the rebirth of the Resurrection. Once upon a time, the list of things forbidden by the Church for Lent was quite extensive: meat, fish, eggs, butter, alcohol, sometimes everything except one evening meal. The days just before Lent became days of excesses as people squeezed in all the fun they could before bowing to the requirements of solemnity and contemplation. And while some people still fast for Lent, giving up sugar, fast foods, or cigarettes, or adding extra prayer and devotional time to the daily routine, it's the party beforehand that everyone still celebrates, from Mardi Gras in New Orleans to Carnival in Rio de Janeiro to Karneval in Köln.

So Ian donned his silver shirt and I laced up my bodice, and we boarded the train, a little self-consciously on my part. No one else at the Bad Breisig bahnhof looked quite as silly as I felt.

But the closer we got to Köln, the thicker the party atmosphere became. After passing through Bonn, there wasn't even standing room left on the train. The beer and wine were already passing freely up and down the aisle, and over the roar of conversation and laughter, we could hear the group in the back of the car singing schlagermusik, loudly and probably off key.

|

They were still singing when we'd detrained in the city, crushed out of the car, down the platform stairs and into the crowd oozing from the train station into the streets. We nearly collided with the first installment of the Karneval parade. The participants wore costumes made of small overlapping squares of fabrics, a riot of colors, a clown family dressed head to toe in Post-Its.

They were still singing when we'd detrained in the city, crushed out of the car, down the platform stairs and into the crowd oozing from the train station into the streets. We nearly collided with the first installment of the Karneval parade. The participants wore costumes made of small overlapping squares of fabrics, a riot of colors, a clown family dressed head to toe in Post-Its.

The open spaces of the city, which not quite two months ago had been overflowing with Weinachtsmarkts, glühwien, and handcrafts, now looked something like a mid-state fair on steroids. A strong performance at one of the game booths could win you something oversized and stuffed; there were treats to eat, crêpes, sausage, cotton candy.

|

There was even a Ferris wheel that would take you high enough to look down on the roof of the Dom. The party towers over the cathedral.

|

Mmmm... warm crêpes. Savory with melted cheese or sweet with sugar, honey, jam, nutella or Grand Marnier. Ian always ordered a savory cêpe while I ordered a sweet one, and then we would pass them back and forth. Sehr Lecker!

A brief walk along the river proved that the rest of the city was deathly quiet. Angling back toward the noise, we found the parade (The same parade? A local parade? Was it one parade looping the city or was it several simultaneous parades?) winding its way through Köln's gay district, where the density of tight jeans and black leather rivals that of San Francisco's Castro. People, packed more tightly together than sardines, spilled off the sidewalk, crowding the endless brass bands marching down the street. A walk that would normally take no more than 10 minutes required more than an hour of careful maneuvers, of waiting until the crowd shifted just so, opening a space to step into.

|

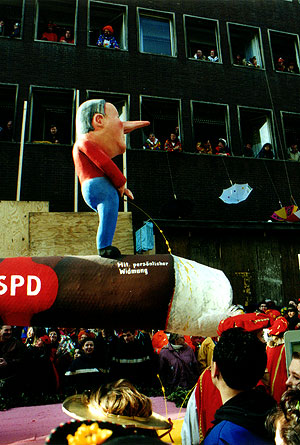

Occasionally, a float would appear between bands. Neither our German nor our knowledge of local current events were ever quite enough to catch the humor. This float is a commentary on one of the German political parties, the Socialist Democratic Party, although I don't know the gentleman "personally dedicating" the cigar, and thus most of the joke is lost on me.

|

The floats made negotiating through the crowd even more difficult: not only were you watching for an opening to move forward into, now you had to watch out above as well. To be certain that everyone got enough candy prior to Lent to tide them over through the deprivation before Easter, those on the floats threw fistfuls of candy into the crowd, with enough force to do damage if you were not paying attention or had forgotten your catcher's mitt. Those with windows overlooking the parade routes lowered umbrellas over the crowd, probably catching far more than those of us on foot below, too tightly wedged to reach up, too closely packed to duck. With the launching of the candy, someone yells, "Alaaf!" and the crowd echoes it back jubilantly, drowning the sound of the next approaching band. It is a cry of pride, dating back some 400 years, to when Köln beat out Düsseldorf for regional supremacy, an old rivalry which still dictates what kind of beer you can drink where.

|

The Teletubbies, in case you missed the ruckus in 1999, are a creation of British television, intent on bringing the joys of TV to the under 4 crowd. These chubby, antenna-ed creatures speak babytalk, run around astroturf hills, and have TV screens installed in their bellies. Gernerally speaking, I distrust anything actively pursuing an audience comprised of people too young to talk. But then I met the teletubbies, lots of them, at Karneval. They seemed nice enough, if a little prone to grabbing; they crinkled a little when they waddled, slurred their words together when they spoke, and smelled of cold beer. Now, I watch their show, again, again!

|

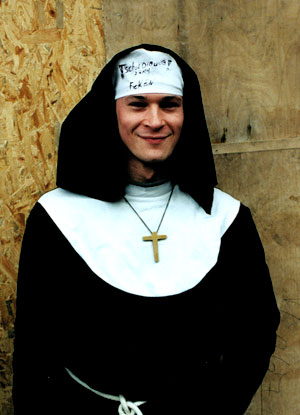

The words you can barely read on this nun's wimple are a line from a popular song. They translate, "Excuse me, um, fancy a fuck?"

|

Karneval fun for the whole family.

|

By the end of the day, Ian had been complemented on his curly hair and his silver shirt, I had two people drop to their knees in front of me and call me "queen," and we'd seen German police helping inebriated partiers to tap the next keg. It might have been a bit early, but what a way to welcome spring!

|