Winter dragged on. I don't remember seeing the sun at all during the entire month of March. Our days were upside down; there was no reason to keep regular hours. The renovations to Rhieneck stretched on, burdened by weather and bureaucracy. The fire marshall wanted this, the landmark preservation society wanted that. Our restlessness must have gotten on someone's nerves. "Take a trip," we were told. "Amsterdam is only a few hours away. You should go see it."

Winter dragged on. I don't remember seeing the sun at all during the entire month of March. Our days were upside down; there was no reason to keep regular hours. The renovations to Rhieneck stretched on, burdened by weather and bureaucracy. The fire marshall wanted this, the landmark preservation society wanted that. Our restlessness must have gotten on someone's nerves. "Take a trip," we were told. "Amsterdam is only a few hours away. You should go see it."

Why not? It seemed unlikely we would miss anything of significance if we went exploring. I had noticed a few brave daffodils blooming around Bad Breisig. The Netherlands, so I'd heard, had field after field of tulips, and this was about the right time of year to see them. Holland had figured in at least one book I'd read as a child; we would go and see canals and windmills and the place where a little boy had saved his town by holding his finger in the dike, stopping a leak before it became a flood. And things would probably pick up after we took time off; after all, last time we took a week to go anywhere, major deals and developments awaited our return.

April Fool's Day found us waiting in the feeble sunshine at Bad Breisig's train station, with two backpacks stuffed with more things than we would need. Rheineck and its hilltop glowed in the yellow light, the castle visible over the still-bare trees. We caught our train to Köln, found one going to Amsterdam, and were on our way. The scenery stayed twiggy and grey until we'd crossed the border.

Even from the train windows we could see the Low Countries were going to be far different from our German home. In Germany, the land goes uphill and down again, sometimes quite dramatically. The Netherlands are unrelentingly flat. While obviously still winter, it was greener than the grey hills we had just left, perhaps because it is closer to the ocean, perhaps because water seems to ooze out of the ground. In the countryside, I could not tell if a waterway was a natural stream or an artificial canal. I lost interest in the canals soon anyway; the new lambs, brilliant white against the young grass, already grazing a bold distance away from Maa, seemed a promise of Spring, Life, Renewal. I hadn't exactly realized how much of a long, grey, cold winter it had been. Literature has equated winter with death for ages; a lifetime in California just hadn't quite made it clear why.

|

We arrived in Amsterdam and walked out of the train station into a crowd of people selling flowers. After passing stand after stand, bouquets and bulbs and postcards, we encountered Amsterdam drivers. Never mind whether the driver is steering bicycle or automobile, they are all maniacs with wheels. It seemed no one ever slowed down for anything. They leaned on their horns or rang their bells and raced around corners, careening past people too slow to have moved out of the way. Dodging through the traffic, we merged into the pedestrian flow creeping down the sidewalk away from the train station.

We arrived in Amsterdam and walked out of the train station into a crowd of people selling flowers. After passing stand after stand, bouquets and bulbs and postcards, we encountered Amsterdam drivers. Never mind whether the driver is steering bicycle or automobile, they are all maniacs with wheels. It seemed no one ever slowed down for anything. They leaned on their horns or rang their bells and raced around corners, careening past people too slow to have moved out of the way. Dodging through the traffic, we merged into the pedestrian flow creeping down the sidewalk away from the train station.

We had been living in Europe for five months. And suddenly I felt like a first-time tourist, fresh off the plane. My German was nowhere near anything approximating fluency, but I had become accustomed to the sound of it around me, even if I couldn't understand it. I could read enough to pick up the meanings of most signs. Now, after only four hours on a train, everything sounded different, and I was relying on pictograms and looking for the little flags indicating information in English. I was a fish out of water all over again.

|

Fortunately, we were staying in a smaller town, fifteen minutes away by train. Haarlem is easier on the senses after the overload of Amsterdam. Without the press of people on all sides, I could check out the buildings, absorb the atmosphere, hear the Germanic roots in the Dutch language. Exploring Europe might not be so scary after all; it might, dare I admit it, be fun.

Fortunately, we were staying in a smaller town, fifteen minutes away by train. Haarlem is easier on the senses after the overload of Amsterdam. Without the press of people on all sides, I could check out the buildings, absorb the atmosphere, hear the Germanic roots in the Dutch language. Exploring Europe might not be so scary after all; it might, dare I admit it, be fun.

Our hotel in Haarlem faced the Grote Markt, the Main Square. After a generous egg and bread breakfast the next morning, we headed out to catch the train back to Amsterdam and see the sights. But first we had to make our way through the market which had sprung up like so many strange mushrooms while we ate. The window by our table looked over the square, and we watched the merchants set up their stands. The construction materials have probably changed somewhat, resulting in metal pipe supports and plastic tarp roofs, but the Monday textile market probably has not changed much since the 17th century heyday of the Dutch textile trading empire. Most stands that morning sold interior design goods: towels, linens, and length upon length of fabric for upolstery and drapery. As I am always on the lookout for fabrics to add to my quilting stash, I browsed the aisles but bought a couple of covers for throw pillows instead.

|

Amsterdam wasn't nearly as frightening the second time around. Spring was making significantly better progress breaking through the cold gray of winter here than in Germany. With the wind blowing in off the North Sea, the weather was certainly not warm, but early flowers and the green haze of emerging leaves let me forgive the overcast and the chill.

Amsterdam wasn't nearly as frightening the second time around. Spring was making significantly better progress breaking through the cold gray of winter here than in Germany. With the wind blowing in off the North Sea, the weather was certainly not warm, but early flowers and the green haze of emerging leaves let me forgive the overcast and the chill.

We visited the Anne Frank House, now a museum in memory of the people who hid from the Nazis in the Secret Annex for more than two years. By making one person's story real, by giving it shape and texture, the Holocaust becomes an honest tragedy, more than an abstract horror the mind cannot accept. I've studied the facts of the Holocaust and some of the literature that has come out of it, and few things convey its depth and breadth as well as the Annex hidden behind the swinging bookcase and Anne's empty room, the walls still paperred with the postcards and magazine clippings of her favorite movie stars and celebrities.

My mind must have remained with the pages of Anne's original diary and the display of all its various translations, for I didn't notice much of our walk across town. Something caught my attention, something lacy winking in the corner of my eye, and when I looked up I discovered we were in the middle of Amsterdam's Red Light District. Either it was too early in the afternoon or most of the girls were busy; many glass doors had their shades drawn. We took advantage of the lack of bouncers and bodyguards to take a few pictures. Be warned: we were in an X-rated neighborhood, and these pictures are of an adult nature.

We wandered out of the Red Light District in search of art. And a snack. Some of the coffeeshops we passed were quite pungent and even I was getting the munchies. We found a man selling very tempting brownies; we bought one and received an "of course, silly" look from the baker when I attempted varifying that they were "just chocolate."

|

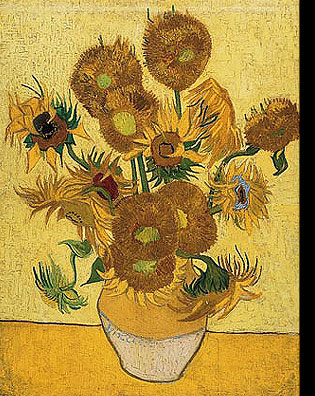

Less than an hour and a half before closing, we walked into the Van Gogh Museum. The Dutch love this native artist, even if he did abandon the dreary murkiness of the Netherlands for the sunnier south of France. They've even put a variation of his famous sunflowers on the back of the 50 guilder note. (The Dutch have some of the world's most colorful currency, at least until the Euro goes into circulation.)

Less than an hour and a half before closing, we walked into the Van Gogh Museum. The Dutch love this native artist, even if he did abandon the dreary murkiness of the Netherlands for the sunnier south of France. They've even put a variation of his famous sunflowers on the back of the 50 guilder note. (The Dutch have some of the world's most colorful currency, at least until the Euro goes into circulation.)

The museum is a chronological review of Van Gogh's life and art. The tour begins with a room full of dark canvases, painted while living with his parents among the simple people and the hard rural life of southern Netherlands. It wasn't until he moved to Paris and fell in with the Impressionists that his works discovered color and he began to paint in what would become his distinctive style: heavy brush strokes and bright contrasting colors laid next to each other.

Eventually, the activity of Paris began to bother him and he moved south, hoping to concentrate on his art. But the isolation, combined with his own inner demons, burdened him and his work turned darker, more surreal. My favorites among his paintings include these sunflowers (pictured), painted just before he checked himself into a mental hospital, and "Crows Over a Wheat Field," completed just before he shot himself.

At the end of our tour, I wanted to sit down and just quietly be; to jump from his final paintings back into the rush and noise and reckless drivers of Amsterdam would be jarring. But the museum guards seemed intent on locking up, and we moved on. Perhaps a little stroll through a park, away from the cars, would ease me back into normality, away from Van Gogh's madness. Instead, we encountered a cluster of vendors selling yogurt drinks and risque postcards, thus completely ruining my chances of a gradual re-entry to reality.

|

The next day we took the train to Zaanse Schans, a preserved 17th century community nestled into a curve of the Zaan River. Featuring several antiques stores, a clock museum, a wooden shoe demonstration, and a small collection of residences set back in early spring gardens, the village clings to a bit of land carved by canals. Paths lead from island to island over small foot bridges and the tiniest drawbridges, the weights and pulleys low enough for boat traffic to raise the bridge without calling for assistance. Moveable bridges also eliminate the need for fences: remove the path over the cannal and confine the flock to an island of grass.

The next day we took the train to Zaanse Schans, a preserved 17th century community nestled into a curve of the Zaan River. Featuring several antiques stores, a clock museum, a wooden shoe demonstration, and a small collection of residences set back in early spring gardens, the village clings to a bit of land carved by canals. Paths lead from island to island over small foot bridges and the tiniest drawbridges, the weights and pulleys low enough for boat traffic to raise the bridge without calling for assistance. Moveable bridges also eliminate the need for fences: remove the path over the cannal and confine the flock to an island of grass.

Walking by one building, we met a new kid, who carefully pranced away from his mother, paused, looked back, and decided we could not possibly be a threat if she was ignoring us so wholeheartedly. Such white fur against the green! Such tiny feet! Such curiosity and such instinct - he was next to Mama in a flash when I stood up.

At its peak of productivity, during the height of the Dutch trading empire, the area surrounding this town hosted some eight hundred windmills, producing everything from oil and mustard to color and paper. According to one story, the paper of the original American Declaration of Independence came from this area. Now there are only 13 remaining mills to testify to the days before steam technology. As we walked toward the closest, a steady thump-thump-thump reached out to greet us.

|

It was louder inside, of course. De Kat is a color mill, quite possibly the last wind driven color mill in the world. The wind caught in the sails outside turns a series of gears driving the machines inside. The faster the wind, the more machines the miller can use at one time. Since the wind was little more than a stiff breeze, there was only one machine in action, an overgrown chisel lifted up and dropped repeatedly onto a block of a deeply red colored wood. Later, the resulting splinters would be ground into a fine powder which would be sold as pigment for paints and fabric dyes.

It was louder inside, of course. De Kat is a color mill, quite possibly the last wind driven color mill in the world. The wind caught in the sails outside turns a series of gears driving the machines inside. The faster the wind, the more machines the miller can use at one time. Since the wind was little more than a stiff breeze, there was only one machine in action, an overgrown chisel lifted up and dropped repeatedly onto a block of a deeply red colored wood. Later, the resulting splinters would be ground into a fine powder which would be sold as pigment for paints and fabric dyes.

We walked through the mill, getting as close as we dared to the whirling gears and moving machinery. Naturally, since the place is entirely constructed of wood, down to the last tooth on the last gear (making it easy to replace a broken tooth by popping the old one out and the new one in and barely interrupting production), and everything is covered in fine wooddust, pictographic signs frequently reminded us not to smoke. Beyond that, we were welcome to watch the gears go around, peer out the tiny windows, sneeze occasionally, wander around the decking outside, and admire the ropes that the miller uses to turn the sails of the windmill into the breeze. And don't forget to buy a little pile of colored powder on the way out.

We spent the rest of the day wandering through Haarlem. There was a fabulous little cheese shop selling goudas of all ages and flavors, everything from young and smooth to sharp and aged, from cheese with basil to cheese with carraway. We accidentally stumbled upon the Ten Boom family watch business and peeked through the windows of the accompanying museum commemorating one Christian family who hid Jews during World War II.

|

Returning to Amsterdam the next day, we visted the Rijksmuseum, "The Netherlands' National Treasure House." Home to some 1200 exhibits, covering everything from Dutch art to Dutch history and including items collected from all around the world by Dutch traders, the Rijksmuseum could easily keep visitors busy for days. As we only had the morning, we focused on the Dutch art's Golden Age, the paintings of the 16th and 17th Centuries.

Returning to Amsterdam the next day, we visted the Rijksmuseum, "The Netherlands' National Treasure House." Home to some 1200 exhibits, covering everything from Dutch art to Dutch history and including items collected from all around the world by Dutch traders, the Rijksmuseum could easily keep visitors busy for days. As we only had the morning, we focused on the Dutch art's Golden Age, the paintings of the 16th and 17th Centuries.

Most of what we saw were landscapes, still lifes, and "snapshots" of ordinary existance among the merchant class. Newly Protestant at that time, the country had no taste for paintings of saints and Madonnas; instead, there are an incredible number of paintings featuring food painstakingly detailed down to the last crumb. Many of the works capture quiet moments, such as Vermeer's "The Milkmaid" (pictured). We may have been on a schedule, but much of what we saw begged us to slow down, to take in the details, the play of light, the beauty of simple things.

|

The Rijksmuseum includes what our guidebook labelled a "thoughtful brown soup," a collection of paintings by that other renowned Dutch artist, Rembrandt. He painted portraits, of course, including the famous "Night Watch," but his heart doesn't seem to be in the faces and the lace collars that paid the bills. His uncommissioned religious paintings, such as the somber "Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem" (pictured), suggest his passions lay more in the search for the spiritual among the earthly. This is not only a heartsore prophet, but an artist wrestling with dark, complicated questions ignored by a nation high on commercial success. In a time of wealth, perhaps Rembrandt was the only one daring to imagine what might happen when the good times ran out. Since no one likes a naysayer, the man whose paintings now sell for millions apiece sold his furniture to pay his debts and died misunderstood.

The Rijksmuseum includes what our guidebook labelled a "thoughtful brown soup," a collection of paintings by that other renowned Dutch artist, Rembrandt. He painted portraits, of course, including the famous "Night Watch," but his heart doesn't seem to be in the faces and the lace collars that paid the bills. His uncommissioned religious paintings, such as the somber "Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem" (pictured), suggest his passions lay more in the search for the spiritual among the earthly. This is not only a heartsore prophet, but an artist wrestling with dark, complicated questions ignored by a nation high on commercial success. In a time of wealth, perhaps Rembrandt was the only one daring to imagine what might happen when the good times ran out. Since no one likes a naysayer, the man whose paintings now sell for millions apiece sold his furniture to pay his debts and died misunderstood.

We finished our tour of the Golden Age, collected our packs from the coat check, and headed off through the rain to the train station. Time to see the flowers! Famous fields of tulips! Kuekenhof, the Spring Garden of Europe, was just a short train ride to the south. Perhaps by the time we got there, we would have left the rain behind. I crossed my fingers and hoped the clouds would clear in time for afternoon sunlight and lots of pictures.

But the clouds stubbornly refused to move. The weather in Leiden was no better than in Amsterdam, possibly even worse. We stood at the front door of the train station, looked out at the grey sky, the chill wind, the falling rain, and couldn't convince ourselves to walk outside. Clearly a change of plans would be just the thing. Let's see ... Belgium's near here, isn't it? And there's a train leaving in less than an hour? What's in Belgium? Hmmm... pancakes, chocolate, and a town frozen in the Fourteenth Century. This traveling idea is sounding better and better all the time.

|